I’d like to share an observation about new technology adoption, the stages that we seem to follow merging them into our lives and businesses, and what this might mean as we look to some of the exciting technologies du jour (depending when you read this, that might be something like AI, or something I can’t even imagine).

Years ago, I was introduced to a framework for behavioural change from Cohen Brown which, among other things, pretty simply broke change down into 4 types: More, Better, Different, Less (MBDL). So, if you were wanting to change a process in some way, you could think about what you wanted to do ‘more’ of in that process. Or ‘less’ of. Or ‘differently’ or ‘better’. As I say, quite simple, but effective in breaking larger change down into smaller manageable pieces.

While originally intended as part of a wider sales process framework, I’ve found myself referring back to this MBDL concept many times over the years as a starting point for everything from more focused discussions on change, to forming action plans, to communicating target architectures, to thinking about what can be done to move complex things forward.

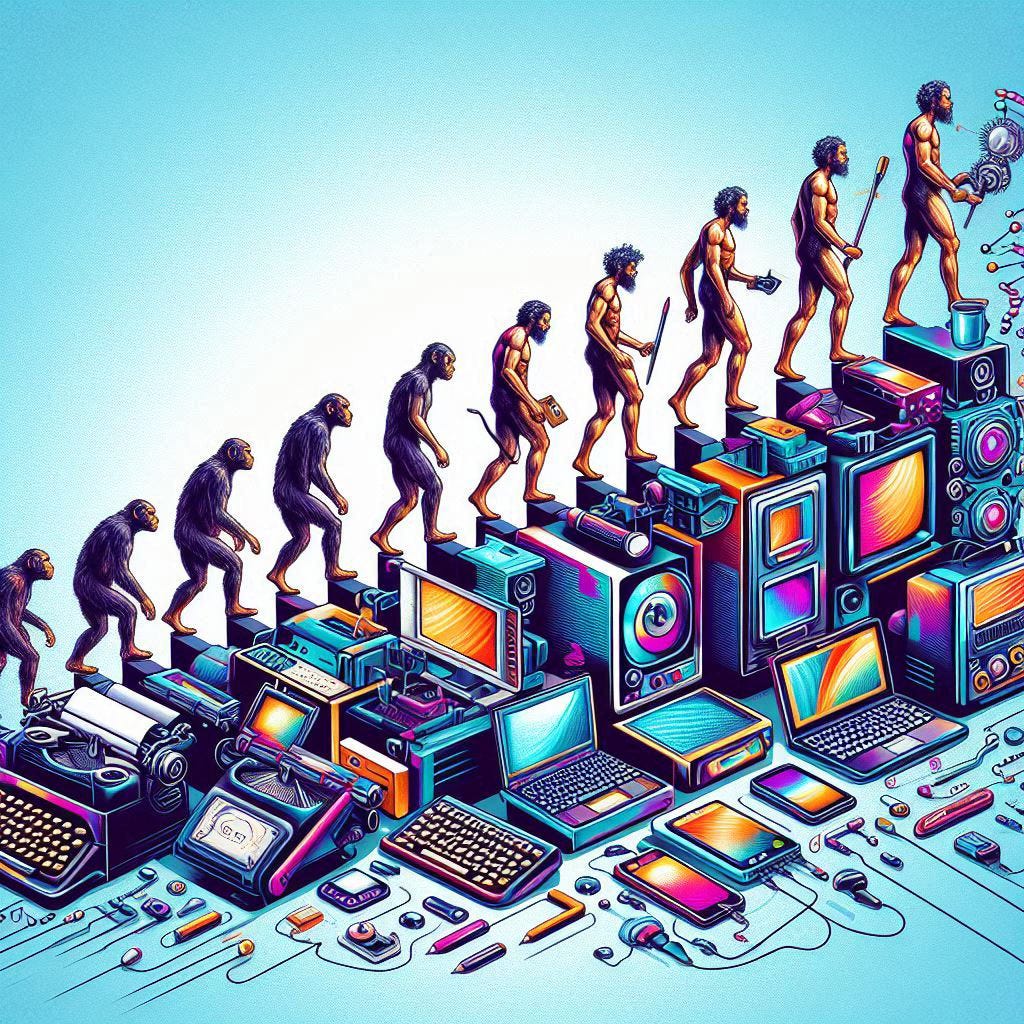

And more recently it’s made me think about the evolution of emerging technology. In fact, I’ve formed a bit of a hypothesis that the four MBDL terms might even be a good way to think about the stages of new technology adoption. It’s just a hypothesis, but seems to stand up to my own observed experience, and I’d like to explore it with you to see what you think.

More → Better → Different….

The first thing we seem to do with new technology is more. More of what we used to do through using the new capabilities to enable, amplify or automate the delivery process. The web enabled us to share more academic papers that were still written in the same way as on paper. Email enabled us to send more inter-office memos, just without the physical paper and ‘carbon copies’ (which is what the CC stands for, in case you are a generation or two younger than me). This applies to non-information technology technologies too: the car comes on the scene, and we travel more. The printing press, more books. Electric lights, more daytime activities carried into the night.

If seems that if we then persist with evolving the technology’s capabilities and are open to changing some of how we do things, we start to get to better. This is a bit more subjective, but email evolves and we start sending better emails with rich text and images helping convey increased complexity in our message with relative ease. The web evolves and we start creating better and more engaging ways to share content and larger datasets. Our books get pictures, our photos get crisper, our online shopping enables access to better prices and a better selection of products.

Eventually, if the technology doesn’t die out at that stage, we get to different. This is where the innovation really starts to show since, as I have said before, the definition of the word involves changing established ways of doing things. So, we have different ways of producing music, or of holding meetings, or of managing customer queries. We start to live differently because of planes, trains and automobiles. We play sport differently, form relationships differently, and relate to each other in different ways than we have before.

…→Less?

It seems that it takes going through all those stages before we actually get to less of the original activity…if at all. Email didn’t lead to less inter-office memos until we actually had a different way of communicating (e.g. corporate instant messaging tools). I mean, if you print out an email, it looks pretty much identical to that of a printed memo from back in the day, depending on your font choice. Whereas, printing a Slack thread (if you can even do that?) wouldn’t look like any memo you’d see on a 1960’s movie or TV show, right?

And then, even if we do get to less of the original pre-new technology activity, it seems to me that the underlying fundamental job that was being done might never get to less. We don’t communicate less because of email. We don’t have less meetings because of Zoom. We don’t travel less because of cars, or work less because of automation. We don’t have less music or less entertainment.

The manner by which we complete these jobs may change, quite dramatically (eventually). But the end that the job served may still endure - particularly if there is enduring value in that end being achieved.

So what, now what?

How often is a new technology heralded with promises of ‘less’, though? That if we just adopt and use the new tech in the right way, the job will reduce and fade away? Yet, that rarely seems to be the case. There are definitely efficiency gains, and if the toil aspects of the job can be reduced, then the underlying job is much easier to perform or scale. Maybe a slight variation of Parkinson’s Law means that we, ultimately, will continue to find ways to fill our time with jobs, regardless.

I don’t see this as being necessarily negative, though - quite the opposite. If my hypothesis holds, then this all bodes pretty well for us as AI (or, insert technology du jour) ‘comes for our jobs’, doesn’t it? I mean, is it coming for our jobs really? Or is it coming for the activities we perform as a means to achieve the end of the underlying job itself? Maybe it is just the means that is changing, but the underlying value is still needed.

If you see your job as being the activities you perform, can I suggest to look a bit deeper at the underlying purpose and value? Accountants, for example, really provide accountability and advice through their structured work with numbers. Lawyers provide counsel and certainty through nuanced understanding of the law. Doctors provide help and healing through the appropriate application of medicine. Do we need less accountability, advice, counsel, certainty, help or healing? Will we in the future?

Unlikely.

So, I’m left wondering: as we find better ways of doing more, differently, whether that could make us spend some time thinking about whether the underlying purpose is something we actually want to do less of at all. And, if not, then perhaps some of the fear can be displaced with excitement and imagination as we look to deploy new technologies in ways that help make things better.

I remember the first fax machines. We thought they were great for sending building plans to clients (I worked at a commercial real estate agency). Nobody thought to use them to send letters!